Multiple Application Scenarios of Strain-Sensitive Conductive Materials

I. Smart Sensing Field: Accurate Capture of Mechanical Signals

Multiple Application Scenarios of Strain-Sensitive Conductive Materials

The materials are fabricated into films or coatings and attached to the surfaces of key components such as robotic arms, bearings, and pipelines to monitor vibration, deformation, and stress distribution in real time. For example, when applied to the cylinder block of an automobile engine, it can capture minor deviations in piston movement through resistance changes, issue early warnings for wear faults, and reduce operation and maintenance costs. When the material is laid on the surface of wind turbine blades, it can accurately detect the bending deformation of blades under strong winds, avoiding the risk of fatigue fracture.

It is used for structural health monitoring of large-scale constructions like bridges, tunnels, and dams. Strain-sensitive conductive composites are embedded in concrete or pasted on the surface of steel structures. When the structure undergoes deformations such as settlement and cracks, the resistance of the material changes synchronously. Data is uploaded to the monitoring platform in real time through wireless transmission modules to achieve disaster early warning. For instance, a cross-sea bridge adopted carbon nanotube/epoxy resin-based strain-sensitive materials, which successfully detected micro-strains of bridge piers under wave impact with a response speed of millisecond level and detection accuracy superior to traditional metal strain gauges.

It enables the pressure sensing function of flexible touch screens and smart wearable devices. For example, embedding silver nanowire/polyurethane composite strain materials in smart watch straps allows users to answer calls and switch functions through the bending deformation of their wrists. Applying this material to the hinges of foldable smartphones can detect folding angles and forces, optimize screen display adaptation logic, and improve device durability.

II. Flexible Electronics and Robotics Field: Endowing Equipment with “Sensing and Adaptation” Capabilities

As the core sensing layer of electronic skins, it can simulate the tactile function of human skin. For example, laying graphene-based strain-sensitive materials on the skin of bionic robots enables them to detect the hardness, texture, and contact pressure of objects, helping robots complete precision grasping tasks (such as grabbing eggs and glass products). Integrating this material into flexible OLED screens can achieve pressure-sensitive dimming and trigger different functions through multi-point pressing, enhancing the interactive experience.

Traditional rigid robots struggle to adapt to complex environments, while strain-sensitive conductive materials have both “sensing” and “driving” potential. For example, strain-sensitive conductive materials based on ionic gels generate deformation when voltage is applied (driving function) and can sense the degree of their own deformation through resistance changes (sensing function). They can be used in the flexible arms of minimally invasive surgical robots, which can not only precisely control the movement trajectory but also sense the contact pressure of tissues to avoid damage. In underwater exploration robots, the flexible fins made of this material can adjust the swing amplitude according to water flow pressure, improving navigation stability.

III. Medical and Health Field: Non-Invasive Monitoring and Intelligent Rehabilitation

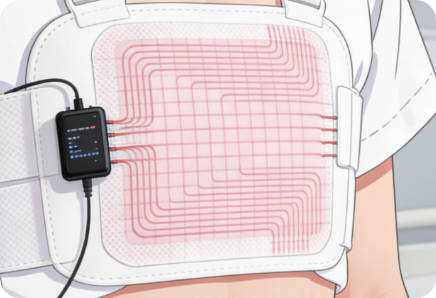

They are made into flexible patches or wearable devices to monitor human physiological signals in real time. For example, chest patches made of carbon nanotube/polylactic acid composite strain materials can monitor respiratory rate and depth through deformations caused by breathing, which is suitable for the monitoring of sleep apnea syndrome. Wristband sensors made of these materials can capture changes in heart rate and blood pressure through micro-deformations caused by pulse beats, and their flexible texture fits the skin, offering better wearing comfort than traditional sensors. In maternal and infant monitoring, fetal heart rate monitoring belts made of this material can non-invasively capture abdominal micro-strains caused by fetal heartbeat, reducing radiation risks.

It helps patients with limb dysfunction conduct rehabilitation training while realizing the quantification of training data. For example, embedding strain-sensitive conductive materials in rehabilitation gloves allows the deformation of finger bending to be converted into electrical signals when patients wear them. The joint movement angles and forces are displayed in real time through an APP, helping patients adjust training intensity. For patients with limb stiffness after stroke, combining this material with pneumatic actuation can adjust the driving force according to the feedback of patients’ limb deformation, realizing the integration of “passive training-active sensing” and accelerating the rehabilitation process. Applying this material to prosthetics can sense the pressure distribution between the prosthetics and the contact surface, helping users better control balance and improve prosthetic adaptability.

IV. Expansion in Emerging Fields: Energy and Aerospace

Utilizing the piezoelectric-strain sensitive synergistic effect of materials, mechanical energy in the environment (such as vibration and deformation) is converted into electrical energy to achieve self-power supply. For example, integrating this material into smart wearable devices can generate electricity through the deformation of human movement to power the devices, solving the battery life problem. Laying strain-sensitive conductive materials on highway pavements can convert pressure deformation caused by vehicle driving into electrical energy to power road lighting and monitoring equipment. Applying it to industrial pipelines can generate electricity through vibrations caused by fluid flow to power sensor nodes, realizing self-powered wireless monitoring.

It is suitable for structural monitoring and adaptation in extreme environments. For example, embedding strain-sensitive conductive materials in the flexible solar panels of spacecraft can monitor the deployment deformation and vibration of the panels during orbital operation, adjust the attitude in a timely manner, and avoid damage. Laying this material on the surface of composite materials of aircraft wings can detect the bending and torsion deformation of wings in real time during flight, optimize flight parameters combined with meteorological data, and improve fuel efficiency. Applying it to the inner wall of rocket engine nozzles can withstand high-temperature environments and monitor structural deformation during combustion to ensure launch safety.